“You had better STOP that SHIT. You don’t know THE STREET. They will eat you alive. You think you’re going to get away with THAT SHIT? Do you know what’s going to happen to you? You’re going to get FUCKED UP THE ASS. Let me tell you something before you let some man fuck you up the ass: You make sure he LOVES YOU.”

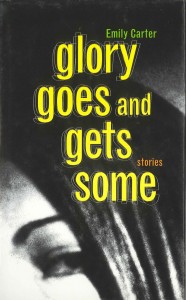

– Emily Carter, “The Bride,” Glory Goes and Gets Some

The first time I read this I was twenty-one years old. I was an intern at a small press in Minneapolis, and reading this story collection was one of my first assignments there. It had just been published. Chris, the editor-in-chief, wanted me to get a feel for the kind of books Coffee House did. In this passage, a random barback lectures the protagonist Glory– a nice Upper East Side Jewish girl and a heroin addict–about the things she’s doing to feed her addiction.

I was shocked by these lines in the way only a nice Midwestern girl raised by fundamentalist Christian parents could be. I had landed this internship in part because I was as clean-cut, as punctual, as good-spirited and enthusiastic, as high-achieving as they come. I had been a Bible Quiz champion, for god’s sake. I mean, my friends and I joked about my Illinois State Bible Quiz Champion crown while too underagedly-drunk to stand, but still. Fucked up the ASS?

I finished the book quickly, but something kept me uneasy as I ran out for lunch, as I did some light filing, as I drove back to my apartment in the stop-and-go rush hour traffic of 35W, as I met up with Mark, my boyfriend, who I believed loved me, and as we went about our evening activities.

Really we had just one activity, drinking, though it had a few variations. His friends came over (mine had long ago declared their refusal to associate with us as a couple), we sat outside–even in November, even in Minnesota–and we drank. Sometimes we’d play Hour of Power, a game in which the participants must take a shot of beer every minute for an hour. When we played, it didn’t occur to me that keeping up with these boys, who outweighed me by at least 50 pounds, was optional. Sometimes we’d go to the only bar in town, where he shot pool and I watched. Sometimes we’d just sit on his stoop, drinking and shivering and smoking.

After a few hours, we’d progress to variation A of our one activity: fighting. He yelled at me, mostly. I was too good for him, didn’t I see that? He was flunking out of school and he was always in trouble and everyone was out to get him and his family was poor and I had the world at my feet. He would put his face right up next to mine and raise his voice and it was so overwhelming and we were both so drunk. Bright as I was, I had no context, no worldview complete enough to counter the manipulative nonsense he was feeding me. We were having sex, so according to the way I was raised, that meant we were getting married. I felt this pressure strongly. We would get married, I was sure. I would wait around for him to finish school–it was only an extra year or maybe two at that point–and we would get married. When he wasn’t too wasted he would cuddle up next to me on the extra-long twin mattress that we shared and tell me how pretty I was and sing Dylan, “The Wedding Song.” What more could you ask for? He LOVED ME.

When we weren’t drinking, or when he wasn’t singing Dylan to me off-key, he was systematically seducing every female under the age of fifty in Northfield, MN. The way he explained it, I, specifically the guilt-inducing reproachful beacon of my ‘goodness’, was making him hit on all those other women; I was forcing him to make out with them in corners at parties while I got us more drinks in the other room; it was my fault he spent the night at their houses while I slept in the extra-long twin, alone. This of course made me cry, which took us right back to our favorite activity, variation A. I believed then that pain was the truest measure of the authenticity of any activity and by that rubric our relationship was real, true love at its most profound. What all this had to do with ass-fucking, I had only the faintest idea, but the whole constellation of associations made me uneasy.

Carter uses “fucked up the ass” in that passage as both a literal description of what’s happening to the protagonist and as a metaphor for vulnerability. I was filing that line away, note to self: only let a guy fuck you up the ass if he loves you, the same way I did when informed of any kind of dangerous, shocking, or transgressive behavior: I knew I would do it someday, and I when I did, I wanted to do it right. I did not want to be Alvy sneezing into the coke in Annie Hall. But what was bothering me was that I already was letting Mark fuck me up the ass, so to speak. Every time I made excuses for him, every time I allowed him to say whatever disrespectful thing he liked to me, with every decision I made that depended on him being my future, I was letting him fuck me up the ass. Part of me knew, on some unconscious level, that he did not love me. But it had never occurred to me before reading that passage that the consequences of this could be very grave indeed, that I might, in fact, be eaten alive.

***

The second time I read Glory Goes and Gets Some I was thirty. A woman I met in grad school who had a heroin problem had reminded me of it. “Have you heard of Emily Carter? You should read this book,” she said, rooting around her bookshelves. I don’t know why she recommended it specifically to me; I assumed that she, like most people who give unsolicited advice, was actually talking to herself. I took her recommendation anyway. When I got to “The Bride,” that passage didn’t perplex me anymore.

“The street” can be a metaphor; being fucked up the ass can be a metaphor. But “You had better STOP that SHIT” – no figurative language is happening there. That’s what I like so much about this book and why I press people to read it. Glory really is getting fucked up the ass; she really doesn’t know the street. Glory really does get AIDS; her body turns on her. This is the most exquisite kind of vulnerability; the system that is designed to keep her well is the one that makes her ill. It’s a metaphor, for those of us who are HIV-negative, but for Glory it’s baldly real. Being fucked up the ass is completely ordinary and pleasurable for some people, but for others, it’s a metaphor for the most abject vulnerability. Are Emily Carter’s words, your reactions, these descriptions, your fragility, your SHIT–are they real? Or are they metaphors? Does it matter? In the book, later on, when Glory’s been in recovery for a while, the bar-back’s advice becomes an epiphany of sorts, a marker of a turning point in her life.

***

Some men, when confronted with the neediest, loneliest, Gollum-like vulnerability–the kind cultivated by a chronically unfaithful first love and the ensuing parade of his doppelgangers, then nurtured by a constant, generous application of alcohol–put you in a cab. They say things like, “You’re a great girl, but . . .” Those are the good ones.

Some enjoy the show for a while but run away when the stuff that the antics were designed to hide begin to surface. And there are some men who see that kind of vulnerability and settle in, who tease it out, who exploit it and take advantage of it. I spent most of my years between twenty-one and thirty with those kinds of men. Not unrelated, I had never stopped drinking, even after it was clear that Mark and I would not get married. “You’re really good at drinking,” I was told, more than once, and I took it as a compliment. I thought I was pretty hardcore. But I was not going to get away with THIS SHIT forever.

Self-destruction often seems glamorous. Carter skewers this delusion:

“Like so many other kids gone wrong . . . I thought it glamorous to be self-destructive. Unfortunately, I had also always known that this was a stupid and callow way to think. I knew that self-destruction was a vile method of slumming; I knew that there were people who got destroyed whether or not they wanted to.”

I also sort of knew this, but I never felt as honest, as authentic, as captivating, as when I was being too funny about my needs and faults over a beer or ten. Later I would surprised when joking about these feelings did not make them disappear, though the consequences of trivializing them and the resulting hangovers were very real and getting worse.

I never had the precise dramatic moment of revelation that Glory does when the barback gives her a lecture about sexual practices. Instead my revelation came in a constellation of associations and partially-formulated thoughts: a psychiatrist told me that my symptoms of depression were in fact alcohol withdrawal; I dated two men with the same initials, at the same time–nothing remarkable in and of itself, but one was my (engaged) boss, and the other was an actual criminal who knew, offhand, the legal dollar-amount distinction between theft and larceny. I had a hard time showering and dressing every day and an even harder time leaving my apartment. Something was off, I knew. But I also was, for the first time, devoting myself full-time to writing, and so I thought that mental instability and self-destruction were part of the package, that “being an artist meant I had to do anything for the experience” (Eileen Myles). I thought that what I had was a “passion for the front row seat” (Philip Roth).

I was quoting writers all the time, but the fact that I was producing very little work was what finally punctured the illusion that I was suffering for my art. I had excused my inability to take care of and respect myself as artistic glamour, struggle, authenticity, but what worth do they have if you can’t even leave your bedroom? My problems had nothing to do with where I wanted to sit. No one will take care of you if you don’t take care of yourself, and no one will respect you if you don’t respect yourself. Such a simple realization– “sappy, in fact, unless you took it at face value and simply acted accordingly, in a simple manner,” as Carter writes in “Zemecki’s Cat.”

Addiction, even if it’s just addiction to a way of thinking about yourself and your life, will fuck you up the ass. Those “glamorous” behaviors will never garner you love. They will not make you a good writer; they will not make you a good lover; they will not grant you success. Glamour is no currency in the world of people who live honest lives.

Emily Carter’s protagonists come to this realization too, and their journey is what makes this book so satisfying. “I was taking my meds religiously. I never missed a dose,” we read in “A.” “I picked up my after-care pamphlet. It was all about Stress Indication and Minimization (SIM) and Relapse Prevention Strategies (RPS). Fine then, I’d follow it. I’d wait and see what happened. But certain things had to be dispensed with first,” she writes in “The Bride,” just before the heroine says goodbye forever to her tormented monster-self.