SK: In some ways, I come a little unprepared. There are two things I wanted to bring you but they’re just about me so they’re not very significant, but it’s interesting for me. The original edition of After Claude, which Iris inscribed to me—a very, very nice inscription, It gets me a little tearful sometimes. And then, another thing I discovered in my papers recently that just astonished me, it’s really interesting, so we’ll skip forward quickly. In 1976, the summer of 1976, I wrote a lead article for Esquire Magazine called “The Guilty Sex.” It was about men in the age of that period who had been discovered to be the oppressor sex. I think recently it was republished, somebody found it and said it was prophetic.

EG: What’s it called? I’ll look it up.

SK: It’s called “The Guilty Sex.” And Iris read it, and wrote me a very admiring letter. I mean, really admiring.

EG: Is that how you met though? You met at a party, I read.

SK: I met her at Susan Sontag’s house. It was not a party. She had known Susan in Paris when Susan was involved with what Iris would have called a “truckdriver” named Harriet Zwerling—Susan was. She had come over to Paris from Barnard—which had been a great experience for her, by the way. I think it was the only institution of any kind that I never heard her speak badly of. She loved Barnard.

EG: Our intern who is going to be transcribing this is going to get a kick out of that, because she is currently enrolled at Barnard.

SK: She had wonderful tutoring and help. And she went to Paris to find herself, be a writer, and so forth. And there she met a man who was going to be very influential for a while, now forgotten and long dead, named Alexander Trocchi. And Alexander Trocchi and she had a very passionate affair.

EG: And he’s the author of Cain’s Book, right?

SK: Yes, that’s correct. And he was the sort of prose-Allen Ginsberg, that was the theory. It wasn’t true, but nonetheless that was the theory.

EG: Are you a fan?

SK: I read him when I was an adolescent. No. Probably not. But he was a very, very compelling person. And Iris had a love affair with him. He is the MacDonald of all her books, including After Claude, that’s when she says, “I left my great love MacDonald in Paris,” that’s who it was. She was very fond of him. Very, very fond of him. And he was very instrumental in the dirty book business. The way it was is he lived off of fine and talented English-speaking young writers, and bringing them to Maurice Girodias, and saying “This person can write a dirty book for you, I promise you.” And so he had a string of people who wrote pornographic books of whom Iris became one, because she was his girlfriend. And did a very very good job on them. Alexander Trocchi decided that it was essential that Maurice Girodias publish Samuel Beckett, and he brought one of the books and said “you have to publish this.” And Maurice said “This is not a dirty book! I have no interest in it. You really must understand.” And Alex said “It is going to be of interest to you, because I’m telling you has to be.” He said, “Well, what do you mean?” He said “I will organize a strike of your writers—you won’t see another page—until you publish Beckett.”

EG: And did that work?

SK: And that worked. That’s how Samuel Beckett got published first…by Girodias being blackmailed by Alex.

EG: Can I back up a little bit? I don’t know if you know this stuff, but she went to Barnard and then moved to Paris to find herself and be a writer. What was her background? How could she do something like that?

SK: She was raised in New York. Her father was a professional gambler, so that they would sometimes move into Park Avenue apartments and then have to move out in the middle of the night to a slum, because they had gone from rich to poor in a week. And he met her mother—who lived up until the time I knew Iris, although I never met her. It was a very unorthodox childhood in a sense that it was, unorthodox in that it was Jewish, intellectual in a sense.

EG: And she later became a gambler too, right?

SK: Yes, it seems it was in the genes because she, for many years, lived off of professional gambling. One of her ex-boyfriends, I don’t remember his name… Jerry Robinson. Jerry Robinson was sort of a mathematical phenomenon. A massively brilliant mind and memory for numbers and for calculations. And he made a team of Iris. He worked at IBM, he working for their computer systems. But he loved Iris and they would go out and gamble together, and with his fantastic ability with numbers and her fantastic cool, they got into quite high stakes. They often gambled with Woody Allen.

EG: Gambling … poker?

SK: Poker. Well, it didn’t always work. You would hear about Iris being a little upset about last night. Yes, she was a gambler. And I don’t know how long she played in those games. Once Jerry was off the scene—Jerry then married a friend of hers. She was the daughter of Dore Schary. Her name was Jill Robinson. She wrote novels. Quite lousy novels. And Jill was married to Jerry Robinson. Everything sort of dissolved the team of the dynamic duo that conquered the poker tables.

EG: Circa when was this?

SK: The date of After Claude was about 1976. Right around the time I wrote “The Guilty Sex.” I would say ’72 through ’77, ’78. But after the book published, it was before then. In fact, I would say 1970 through… whenever she got back from Paris. Until maybe 1974 or 5. That would be my rough guess.

EG: I distracted you, I’m sorry. Let me get back to when you met.

SK: I had met Susan through some of my writer friends, and I had become a protégée. That’s really what I was. At that stage of her life, she loved protégées and did very well by them. She was very fond of them at the time and helpful to them.

EG: One of our picks was Sigrid Nunez’s book about being a protégée of hers.

SK: By Sigrid Nunez? Sigrid was one of them. Her book is very good and very credible. There was a lot that I didn’t know while Sigrid was living with Susan. A lot was her romance with David. But I believe it, I think it’s a very honest book.

So I met Iris then, probably in ’67. Iris was talking about a piece that either Nabokov had written about Girodias or Girodias had written about Nabokov. Either Nabokov was claiming that he was a filthy French thief and pornographer not worthy of attention, or Girodias calling Nabokov an ungrateful pretentious bully. I think that piece was, they were talking about it. Iris claimed that she had edited parts of Lolita.

EG: Do you think that’s true?

SK: I was very skeptical about it. I’ve never seen any information about it.

EG: Ah, who knows.

SK: But Maurice would certainly not let anyone know that that was going on. And Iris, she had all kinds of character qualities, but she didn’t lie. I don’t remember, I think she had said some trivial white lies but I don’t remember her lying at any time—

EG: So a brilliant poker player, but not a liar.

SK: Generally when she said something, you could see that there was an Iris twist on it. The facts were right. Some time afterwards I bumped into her and we started having coffee. Then I came to visit her and I fell under the Iris spell.

EG: But not a romantic thing?

SK: Never a romantic thing. Never. I was too quote smart for that unquote. Someone involved in a romantic relationship with Iris was interested in trouble.

EG: What kind of trouble?

SK: Well it didn’t happen often enough for me to really know. She was very quick—not in a Harriet way—but very quick to feel herself mistreated. Often in situations when she was not being mistreated. I’ve never thought of this before, that’s a good question. I don’t think Iris was prepared to change her life for anybody. For any reason. She liked having interesting lovers, and she had a long string of them. But the idea of Iris moving in with somebody, or somebody moving in with her, which of course is one of the basic themes in After Claude… It was a thing unimaginable. Interrupt any time with any questions you want.

EG: Where was the apartment exactly?

SK: Apartment Number 8. Cornelia Street. It was on the sixth floor. It wasn’t particularly an arty building, but Iris was there. And she lived there the entire time that I knew her until her death. I could draw you a picture of every piece of furniture. So. It was a one-bedroom, rather modest apartment with some very nice things, usually given to her by exes. There was one guy who was a dealer and she had rare Chinese furniture and tapestries and silkscreens and these gorgeous long, Chinese chairs that she sat in along with a tapestry hanging. But the spell was what was interesting. I’ve since come to recognize a little more about it than I knew. You should probably read the Emily Prager introduction. When I began, I thought god, Emily Prager was a terrible choice. But then I read the introduction, and she’s not bad about the spell and why friendships with Iris were tiring.

She rarely left the apartment. She drank quite a lot. And in that stage of my life, I did too. And she was an absolutely wonderful talker. She was obviously very, very intelligent, and an exchange with her about anything would take you places you were not expecting to go. Always. You want to talk about Anthony Weiner, Iris would be in another chamber altogether and it would be a pretty interesting place. So, that was very attractive. She was also… She was beautiful. As I was thinking about her looks, I was thinking of the line from Antony and Cleopatra in Shakespeare: “Age cannot wither her nor custom stale her infinite variety.” That was it. She had gray hair when I met her. Always did. She seemed never to change. She was just this beautiful woman who was on the verge of middle age. And it never stopped. I mean, I didn’t see her in the last years. But I saw her once, at some opening or something. She was more white haired, but she was certainly not aged in any obvious painful way.

EG: Maybe the secret is never leaving your apartment.

SK: Well, that had something to do with it. I’ve since learned that many people who are agoraphobic, which she certainly was, develop the ability to spin a spell that will keep people from leaving.

EG: Oh, that makes sense.

SK: And that’s what happened to me. I would go to see Iris for a cup of coffee at three, and leave at three a.m. And that was quite a characteristic.

EG: Oh, I know people who are like that. And you do start to feel sort of trapped, right?

SK: I felt trapped, but I was in such an interesting trap. But it was a trap. The day was destroyed, my next day was destroyed. And she had not wanted me to leave at three o’clock, even. Not that she could have lived with anyone, but. The spell was extremely sound.

EG: But then you said it would end, right? It was finite.

SK: Iris had, I would say, to put it crudely, Iris actually had a very wide sadistic streak. And once she had someone under the spell, that person could expect that her real attraction for them would involve a fair amount of humiliation as well.

EG: How would she effect this humiliation if she didn’t leave her apartment much?

SK: You could talk about something that she could take into the equivalent of the conversation and formulate how you’re wrong. How you’re wrong in your typical way of being wrong. And shake your confidence. She was very good at shaking confidence. Making one stop believing in oneself. It could be quite frightening. I think that’s what happened with Emily Prager. This happened quite often. And so, in the end, I felt bound into a kind of S&M relationship with her. Really kind of intellectual. I remember thinking at one point, “Well, this will only end when either she dies or I die. And I can’t stop it.”

EG: Clearly it ended much sooner. What happened?

SK: It ended much sooner in the sense that I just thought, “I’m just not going to do this anymore.”

EG: One day, you just…

SK: Well, it took me months. But I gathered my energy and decided, “No more.” I won’t go back. It doesn’t matter how funny she is or how smart or how talented, or how wound up in her I am, I won’t endure another second. And I didn’t. And she was very sad. I would return her letters to her unopened. And it just ended slowly. I would very much avoid going anywhere I thought she was likely to be, but she wasn’t likely to be in most places, so that was not a problem. This makes her sound like a monster. And she was, in a way, a sort of monster. I would not have traded my friendship with her for anything. It was very good, but I know that a lot of my career was in shambles because of her.

EG: For how long?

SK: Ten years.

EG: Ten years?

SK: Ten years.

EG: Why? How? What did she do?

SK: You’d say, “I am working on something—”

EG: Oh, she undermined you.

SK: You would walk in thinking, “I’m really getting somewhere,” and you would walk away wanting to tear it up.

EG: That sounds like a… When you say spell, it’s hardly…

SK: Misery loves company. Anyway, it’s crazy. So, she loved having other non-productive writers around her. That was why I was so blown over by her response to that essay. I came across it recently, in my papers, and it was so warm, so admiring, and so insightful.

EG: And that was after you had…?

SK: No, we were still friends, although things were getting bad. The unpleasant parts were getting more frequent, and more unpleasant.

EG: You said that she didn’t lie.

SK: Not in my experience.

EG: So when she undermined you, did you feel like she was telling you the truth? The truth about your ideas?

SK: That truth is not exactly what you need to undermine someone. What you need to do is make them feel that they’re a fool to think they can do this.

EG: It seems that she was especially good at undermining her own efforts.

SK: Oh, yeah. When I say misery loves company, she was —, she talked about it endlessly. Amusingly, and also painfully. And, for example, she played poker with Woody Allen. But would she have socialized with him? I think not. Because he would have been immune. Or, if he wasn’t immune, he would have known when to leave, when to walk out. And I was a kid, and I didn’t.

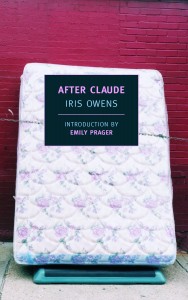

EG: A lot of the books that we end up featuring, sometimes we republish things that have fallen out of print, and sometimes we revive things that were initially published badly for whatever reason… The initial publication of After Claude was not bad at all, as far as I can tell. It was good, right?

SK: Wonderful. It was very well-reviewed. Very well-reviewed. It got a lot of attention in Newsweek. There was a big Newsweek article about it which filled her with humiliation.

EG: Why?

SK: She told the reporter that she was specialized in the years before in being an interesting failure. This was quoted, and it just was a nightmare. She just couldn’t believe that she’d been so indiscreet as to set herself up for that. I myself didn’t think it was going to do her any damage at all, but she did. And then she got into a war with [her publisher] Roger Straus, as she did with anyone who was very generous with her. She would always wage war.

EG: She couldn’t accept generosity?

SK: Not really. She could accept admiration, and she could accept special experiences, but Roger Straus—the real editor was Henry Robbins, not Roger. Roger had a kind of confidence that Iris was very interested in puncturing, and it didn’t work. She could have had a great career … but she shouldn’t have fought with Roger.

EG: No, that seems like a tactical error.

SK: It was impossible to stop her from doing these things. She believed, like a lot of people at that point, she believed in magic. She thought that since she had a book that was very funny—that could have a wide audience, that had been widely reviewed in national publication– she ought to be the new Stephen King. And when she wasn’t, when it was just another novel sending under ten thousand copies, like most novels do, she believed she had been betrayed. And all of this is paranoia. Let’s talk about something nice. What next?

EG: I don’t know if this counts as something nice, but you did sort of bring this up, and I have to ask, although I think I’m already getting a sense that I know the answer. I’m sure a lot of people who read Emily Prager’s introduction and then read the book think that possibly, Iris was Harriet-esque. But it sounds like in many ways, she really wasn’t. What do you think her relationship to that character was?

SK: Well, first of all, she was about ten times more intelligent than Harriet, which means that she would not say the preposterous things that Harriet said, although she might think them. She knew her own depressedent capacities and how to laugh at them, so that Harriet is always, almost on the edge of being right, but she’s preposterously wrong at the same time. That was the gift that she saw. And it went straight into the heart of it, that who she was. It’s hard to say exactly how, but it was. She loved to be amused, and she was very amusing. Irony and self-irony played no small role in that. Her own self-irony would be way above Harriet’s in terms of its mental contact, but the twist was always there. She would give other people a hard time, but she gave herself a hard time too. Sometimes hysterically, and sometimes with a kind of twist of the knot. Anyway, should we talk about After Claude? At a certain point, Iris used to go to a string of establishments in the Village where she was certain to be given things from the owner, because they were very in love with her. And one of them was a bar that still exists called The 55. And Iris would go to The 55, which was just essentially just a long hall, old, reeking with alcohol. I was never actually in it, but I’ve noticed it still there. She would go and shut the place down at three a.m., and come home with someone, often. She did in this case come home with a guy who I believe was a reporter for maybe time, maybe one of the big glossy publications, and she became pregnant.

I think I was almost the only person she confided this in. She was very, very torn about what to do. But if she wanted the child, she knew this was her only chance. He was a perfectly smart, fine person, who wasn’t interested in being a father, but there was nothing wrong with him. She was really in a dilemma. And she wanted to hash it out with me, so we hashed it out.

I told her two things: I was a little lonely, and crazy, and would have loved to have a child. Loved it—as I later did love having a child. I told her if she had the child, I would join in raising it. I wouldn’t be the father, I wouldn’t pretend, but I would be very present for it all. I also told her that if she had the baby, she would never write another book. Which was true. That touches a little bit about Iris’s relationship to money, which was very mysterious—because how you could sit in those beautiful Chinese chairs year after year and continue to have the flow of cash? So, we went back and forth, and we did a lot of talking about the book that she would never write. I don’t know where I got the confidence to say she would never write a book, but for all I know, I was right.

So she decided to have an abortion, which was still then illegal. I went with her by train to Florida. The guy, I think, was not quite interested in the decision, and not interested in paternity, but I think he was financially quite sound and undertook the cost of all this. She took a train with me going to Florida to have the abortion with a respectable, needless to say, good physician. Then we took the train back, and the emotions coming back were even more complicated than going down. It took a day and a half, or something. One of us started talking about the book she was never going to write. And, I think it was on the train, I’m not sure of this, but she said, “At least I have a first line.” And I said, “Really? What is it?” And she said, “Claude left me, the French rat.”

And I started to laugh. I thought it was the funniest thing I had ever heard. And I said to her, “You have to write this book. It is essential that you do.” She said “But it’s just a line, it was nothing.” I kept saying, “Of course it’s not nothing. It doesn’t come from nowhere, it comes from somewhere. Get the rest of the somewhere out there and see where we’re going.” I pushed on this relentlessly.

So, she at a certain point began to write with tremendous difficulty. By the way, the opening line was later changed. She called me and said “I know that you’re going to be upset about this, but I changed it to ‘I left Claude, the French rat,’ because Harriet would never admit that she had been left by someone.’” So we built on that, and she wrote with great difficulty, but always what she wrote, she knew what she was doing. That is, she didn’t do what I would do, or anyone in a difficult position as a writer, which is write a piece of crap, and and look at it, and say “This is a piece of crap.” I would do that.

EG: At least you can revise.

SK: Yeah, I do revise. But Iris didn’t do that. The pages were heavily worked, and she was paralyzed. I would come in and almost literally pick up the pages from the floor, where’d they had fallen and been stepped on. I’d say, “You’re having a hard time,” and we’d talk about the hard time for a very long time. Then I said, “It’s not going well, but let’s make a deal. I’m going to type what you do every week.”

EG: That sounds like a great deal for her, I don’t know what kind of a great deal it was for you.

SK: Well, I typed very fast. I wasn’t very accurate, but I was fast. I would take these pages to my apartment and type them. I think I typed almost the whole book, at least once or maybe twice because she would do revisions. So what had happened was that instead of my becoming the father of the child who was not to be there, I was in another analogous role, something she wrote in her inscription to me. She said, “To Stephen: for patiently, lovingly, and wisely following this book.” Something memorable, something along those lines that gets me all choked up. There was a structure to that, really. I never typed the end. She didn’t let me see that.

EG: The whole scene?

SK: The last scene, in the Chelsea. And I’m not quite sure why. I can’t even speculate. Except it was for her, everything. The final scene was essential. It couldn’t not be there. Its role was overwhelmingly significant. I think one of the things that is not known now is that, in the ‘60s—and it was one of the things that was in “The Guilty Sex,” although I wasn’t always aware of it, that Iris and I were thinking along the same line, although from completely different perspectives. There was a phenomenon which was commonplace: a certain kind of bohemian underground guy who would gather around a large number of women who were essentially under his spell, and with them he would be highly manipulative. And they were girls, and they were saints, and they were geniuses. It’s a common phenomenon that has now vanished, so far as I know. It was easy, it was just everywhere.

EG: It was sort of unprecedentedly easy then, I think.

SK: It was just like getting a taxi cab. I didn’t do it and I was male, so I wasn’t ‘in.’ I was also very middle class. I’m not interested in bohemia, it can go fuck itself. I did live within it, and I had a great weakness for interesting people, and god knows Iris was interesting. So, she got to that ending, which is, in my experience, the best description of the female orgasm that I’ve ever read.

EG: Okay.

SK: Well, maybe I haven’t read enough. I don’t really know what I’m talking about, but still. She was very interested in, she was fascinated by Masters and Johnson, just absorbed every syllable. Sex was very interesting to her, in a way that it was of course interesting to everyone, but her mind and her artistic spirit wrapped around it in a very powerful way.

EG: I agree with you, I think that the descriptions of the interiority of the character are very psychologically acute throughout the book, but then in that last scene… Very few writers who aren’t just writing pornography write descriptions of sex with a lot of nuanced description of consciousness.

SK: It’s very, very difficult. The writing is really terrific. And I must say after all of this so-called sexual revolution and the like, I managed the estate of the photographer Peter Hujar. In this same year, in ’76, he did a sort of breakthrough triptych calledTriptych of a Male Nude (Bruce de Sainte Croix). It has become famous in the history of photography. In the first, it’s sort of like David in the male nude. Then the second thing is kind of a weird masturbation, which is of this young, passive guy contemplating his erection in a way that is very compelling and interesting. We’re not talking about pornography here. This really wasn’t pornography. The third was a photograph of him masturbating, as he said later, ‘just before the thunder clap.’ It too was a beautiful, remarkable picture. Now I bring this up, because I interviewed him, he’s now in his ‘60s, a semi-retired social worker from the Cape, a very, very intelligent and pleasant person. I interviewed him on film for Peter’s archive. His description of the male orgasm, verbally, was the best I’ve ever heard. I’ve been privileged here, I’ve met two—it was really remarkable, he’s right about everything, have I really never thought about this before? He gets it just exactly right. So that was what was so impressive.

So, she was very filled with anxiety. When she got the —, she went to Florida State with her sister and called me and spent half the night weeping on the telephone because it was such shit, she couldn’t believe it, it was so insubstantial, so trivial, what had she done, how had she deluded herself.

EG: And what were you saying?

SK: I was saying, “You’re not deluding yourself and it’s not insubstantial and it’s not trivial.” I just wouldn’t back down. I was not going to grant her that. She was doing to herself what she could sometimes do to other people, which is look at what they’ve done and humiliate them. It was painful to see that. She gathered steam, she worked better—although never well, it took her a long time. There would be a page every month, or something like that. I exaggerate, I don’t remember.

EG: Three years.

SK: It took a long time. I thought, what Iris needs to do, no matter what — I’m quick to tell people what they need to do, is do this book, establish herself as the comic writer for general fiction, and then do eight more, right away, as fast as possible, using all her resources. And I might as well have suggested that what I need to do is flap my arms and fly to the moon, because it was just an absurd hope.

EG: Do you think drugs would have helped?

SK: Oh yes. She was depressive. She could have used Prozac, I would think. My wife is a psychiatrist—she never met Iris—and thought I was crazy to have been involved with her.

EG: But not in a clinical sense.

SK: No, close. I mean, why do people stay in very powerful and abusive relationships? That’s the question. And I love Iris, I still do. Even though I’m not talking about her very lovingly right now.

EG: I think you’re talking about her honestly. Also, she’s dead, so who cares?

SK: By the way, she died exactly as she feared. She endlessly smoked, and talked about stopping. I must have spent at least ten months listening to her discuss stopping smoking. She was terrified of cancer, and died of double lung cancer, which killed her very quickly. She had known no longer than a week, and was gone.

Enough about that. The book was hilariously funny. I get one mention in it—remember when Harriet is locked out of the apartment, and hires a locksmith to come and the guys comes down the hall, and she says “I had heard that Ilse Koch had a son while she was in prison, but I never hoped to meet the boy.” Do you know who Ilse Koch is?

EG: No.

SK: She was one of the great monsters of the German concentration camps, I think she was in Auschwitz and she was one of the horrendous figures. Imagine that as a compliment.

EG: That’s about as backhanded as it gets.

SK: I always knew that with it, she could have established herself as the comic woman novelist of her period. I had no doubt that she had the equipment for it except for being crippled by her neuroses. She was intelligent enough, shrewd enough, self-composed enough, and talented enough, just lewd enough, that it could have happened. I remember somebody threw a party once for her and Fran Lebowitz, the idea being that the two funniest women in New York should meet each other. It didn’t go well, of course, but still.

EG: They were too alike?

SK: No, actually, they’re not alike. They were friends, but…

When I look back on Iris’s humor… I can’t say what it was. It’s very hard to say what it was. I mean, of course look through After Claude, that kind of stuff happened all the time. But then she’d describe one of Alexander Trocchi’s girlfriends, and how Alex was manipulating this girl, and Alex was, in a way, sort of the prototype for these men. You’d just be listening to this story, and suddenly you’d just be laughing uncontrollably. That was really wonderful commentary, really wonderful, and tragically lost.